By Marty McFly @mcflynews.com | April 8, 2025, 5:15 a.m., est

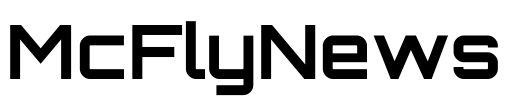

OTTAWA — Trump wants a piece of Canada’s freshwater, and warnings are piling up. With nearly 20% of the world’s supply, Canada sits exposed — no federal protections, no export bans — as climate change accelerates and drought-stricken U.S. states grow thirstier by the year.

“Canada is not a water-secure country”, warns Bob Sandford, chair of water and climate security at the United Nations University Institute for Water, Environment and Health. “We have this myth of abundance. But we’re not nearly as prepared as we need to be for growing threats — both environmental and geopolitical.”

Across states like Arizona, Nevada, and California, prolonged drought and overuse of aquifers have created a crisis that could push Trump and his cronies toward drastic solutions — including sourcing freshwater from beyond their borders.

Trump has already referred to Canada as having “a big faucet” that the U.S. might need to open. While this may sound flippant, water governance policy experts view it as a real warning sign. “We are entering an era of global water insecurity, and Canada is sitting on one of the most coveted reserves on Earth”, says Maude Barlow, former senior advisor to the UN on water and author of Blue Gold: The Battle Against Corporate Theft of the World’s Water. “There will be pressure to share, sell, or exploit those waters, and Canada has no clear, enforceable law to stop it.”

Indeed, Canada lacks any federal legislation banning bulk freshwater exports. The concern is that water could be classified as a tradable good under international agreements like Canada -U.S.-Mexico Agreement (CUSMA). “If we don’t explicitly exempt water from trade talks, it risks becoming a commodity like oil or lumber”, says Elizabeth May, a former environmental lawyer and MP, who has long warned of water commodification risks under trade frameworks.

Environmental organizations have also raised these concerns with data. WWF-Canada, in its national freshwater health assessment, found that over 60% of Canada’s sub-watersheds lack sufficient data to determine health, and many of those that are monitored show “moderate to high levels of degradation”. Elizabeth Hendriks, Vice President of Freshwater Conservation at WWF-Canada, states: “Just when Canadians need our freshwater ecosystems the most, they’ve never been in more trouble.”

Historically, this issue isn’t new. On 25 August 1988, the then Minister of the Environment, the Hon. Tom McMillan, tabled in the House of Commons Bill C-156, the Canada Water Preservation Act. The Minister stated that he was tabling the bill to give legal force to the commitment of the federal government, expressed in its water policy announced in November 1987, that it would oppose large-scale water exports from Canada. Within weeks of its introduction and before it could be considered by a parliamentary committee, the bill died on the Order Paper when Parliament was dissolved on 1 October 1988 on the call for an election. No government bill on the subject has since been introduced in Parliament.

Had it been enacted into law, Bill C-156 would have prohibited the export from Canada of outright large-scale freshwater exports, such as those involving inter-basin transfers between river systems, and strictly regulated small-scale exports, such as those involving shipments by tanker or pipeline. Very small-scale exports, such as water used in manufactured goods and bottled or packaged water, would not have been affected by the legislation.

The bill, which would have been binding on not only the private sector but all levels of government, would have provided for the creation of federal-provincial agreements for licensing small-scale exports. The Governor in Council would have been granted broad regulation-making powers respecting licences, such as: the procedure to be followed in applying for and issuing licences; their duration, renewal, revocation and suspension; fees; the criteria to be used in deciding whether to issue or renew licences; and public hearings and disclosure of information in connection with the issuance, renewal, revocation or suspension of licences.

The Governor in Council would also have been granted the power to exempt from the licensing requirement, by order, “the exportation or diversion of water in the circumstances set out in the order.” The above provision would have allowed very small exports to be exempt from regulation, but would in no way have sidestepped the prohibition on large-scale exports.

No export licence would have been granted under the bill without a thorough environmental assessment.

The bill also contained detailed enforcement proposals and would have provided for penalties of up to $1 million and three months in jail for violators.

In his appearance in 1993 before the House of Commons Legislative Committee on Bill C-115 (NAFTA implementation), Mr. Konrad von Finkenstein, then the Assistant Deputy Attorney General, Department of Justice, stated in part:

… if you trade water in its natural state you put in tanks, or bottles, or something and sell me fresh water that you’ve taken out of a well or something like that, then you are indeed trading in water and it’s then a good and is covered by the GATT, by the FTA, or by the NAFTA. But that’s a good you’re trading…

Water is no different from any other resource. Take a forest, for instance. There’s nothing in the NAFTA, the FTA, or the GATT that forces us to cut our trees down, etc. –you have to play by the rules. You can’t protect your domestic industry, etc. And the same applies with water, you don’t have to trade or anything with it.”

A provision similar to that in the Canada-United States Free Trade Agreement Implementation Act was included in the North American Free Trade Agreement Implementation Act. The latter provides in section 7 that:

7. (1) For greater certainty, nothing in this Act or the Agreement, except Article 302 of the Agreement, applies to water.

(2) In this section, “water” means natural surface and ground water in liquid, gaseous or solid state, but does not include water packaged as a beverage or in tanks.

In other words, according to the Canada’s domestic legislation implementing the NAFTA in Canada, none of the NAFTA provisions, other than Article 302 (tariff elimination), applies to natural surface or ground water.

Critics such as Wendy Holm contend that section 7 of the implementing legislation is insufficient protection without an amendment to the NAFTA itself and that only such an explicit exemption can protect Canada’s water resources from American interests. These critics claim that the domestic legislation is not binding on NAFTA panels and that currently the Agreement itself would be given precedence over domestic legislation.

As earlier noted, the three NAFTA countries clearly stated in their joint declaration of December 1993 that the NAFTA does not apply to water in its natural state in lakes, rivers, etc., since the water has not at that point “entered into commerce and become a good” for purposes of the NAFTA. The federal government has taken this position all along with respect to the NAFTA and its predecessor, the FTA. Nevertheless, critics of the government position remain adamant that water in its natural state is covered by the NAFTA and that nothing short of an amendment to the agreement, accompanied by federal legislation banning large scale water exports, will protect our water resources adequately.

Decades later, no government has reintroduced such legislation. Hence, the concerns of critics have not been appeased by the federal government’s recent announcement of a strategy for seeking a commitment from all jurisdictions across Canada to prohibit the bulk removal of water, including water for export, from Canadian watersheds. Now that we’ve seen just how reckless and erratic Trump can be, the debate concerning water exports and its safeguard, is certainly not over.

Trump’s sudden interests regarding Canada freshwater clashes with the decades-long warnings of Dr. David Schindler, one of Canada’s most respected freshwater scientists, who spent his career exposing how northern aquatic ecosystems are dangerously vulnerable to pollution, overuse, and climate disruption. His research showed that Canadian lakes are far more sensitive to stressors than policymakers assumed. “We risk losing entire freshwater ecosystems before we even begin protecting them properly”, Schindler had warned.

Schindler, consistently expressed concerns regarding Canada’s water legislation and its adequacy in protecting freshwater resources. He highlighted that while Canada possesses significant freshwater reserves, the renewable supply is limited, stating, “While Canada has a large freshwater ‘bank account,’ the interest rate is very low”.

The legal framework for water shared along the Canada-U.S. border is governed in part by the International Joint Commission (IJC). But experts note this body is diplomatic, not binding, and cannot override national trade negotiations. “It’s good for cooperation — but not for enforcement when political pressure ramps up”, said Dr. Adele Hurley, founding director of the Program on Water Issues at the University of Toronto.

With the renegotiation of CUSMA expected to begin soon, the time to act is now, many experts say. “Canada has to draw a red line — no bulk water exports, no trade inclusion, and a federal law to back it up. Otherwise, we risk losing control of one of our most precious resources“, said Sandford.